We infill plants with meaning for many reasons; they remind us of people we’ve loved or times in our lives. Guard seeks to remind us of the stubbornness of life, the human ability to evolve and adapt and ultimately our desire to survive.

– Jodie Carey

Edel Assanti is pleased to present Guard, Jodie Carey’s fifth solo exhibition at the gallery. A site-specific installation of 150 jesmonite sculptures mounted on steel supports stretches across the entirety of the two ground floor galleries, articulating a serpentine path through the space.

Carey produced her latest installation employing a technique called earth-casting: wrapping plants with cloth and thread, the artist created slender, delicate sculptures that are then pressed into the earth’s surface to form a rudimentary mould. The wrapped plants are then removed, and jesmonite is poured into the remaining imprint in the soil. Pale in colour, the resulting sculptures reveal traces of fabric, leaves, stones, and roots with a hauntingly exquisite level of detail.

Exploring notions of ritual and mortality, the tall, elegant uprights evoke the timelessness of standing stone monuments or an army of sentinels, silently registering the passage of time. The subtle tonalities that result from Carey’s distinctive process emphasise the sculptures’ faceted surfaces, revealing their elemental form whilst embodying a sense of impermanence.

Carey’s recent work has explored culturally universal art-making methods including carving, weaving, and wall-drawing. Through revisiting age-old techniques, Carey’s oeuvre emphasises the relationship between object making and commemoration, looking to the physical world as a repository of material memory. Diverting from the history of monumental sculpture, Carey’s work belongs to a female British sculptural tradition that emphasises object-experience and materiality over image-making. Choosing to work with fragile and ephemeral materials, her installations challenge the permanence and solidity traditionally associated with the medium.

Flowers have been a recurring motif throughout Carey’s practice. Earlier works comprised elaborate flower arrangements and bouquets unexpectedly fabricated out of newspapers that have been soaked or dusted with blood, bone or ash. “Flowers are strongly linked to cultural identity and so quickly become synonymous with conflict and atrocity around the world”, Carey notes. “Most recently the sunflower for Ukraine became an instantly recognisable symbol of support. But flowers have always grown amongst the devastation of war. Poppies, carnations, forget-me-knots are all historically bound to conflict and remembrance. We think of these flowers beyond their seasons.”

Referring to soil as the skin of the earth, Carey’s interest in soil as a material is born out of its essential relationship to life and simultaneous ability to embody death. Its complex constitution combines minerals, water, air and the decaying matter of once-living things. In this way, Guard continues Carey’s engagement with concepts of entropy and time, emphasising the universal human urge to commemorate our lives by making an impression on our surroundings.

The New Art Centre

Roche Court

Across geographical and cultural boundaries, textile production in its myriad forms is one of the earliest human technologies, with woven and dyed fibred dating back to prehistoric times. The art of designing textiles has therefore remained a central medium for both utility and creative expression throughout human history.

New Art Centre’s exhibition Common Thread brings together a group of artists each of whose work focuses on the history of textile technology and design, and their shifting values for people across place and time. Exploring the ways which certain textile producing technologies are still in effect, while others are being challenged, the works in this exhibition reflect on the place of textiles both in art, and in contemporary society.

Edel Assanti

London 2019

Over the past decade, Jodie Carey has explored the universal human urge to make an impression on our surroundings. Through site-responsive sculptural installations, Carey’s practice adopts culturally universal, age-old artistic methods of creation, often evoking ritualistic or primitive traditions. Through revisiting these techniques, her oeuvre emphasises the relationship between object making and commemoration, whilst also looking to the physical world as a repository of material memory, silently registering the passage of time.

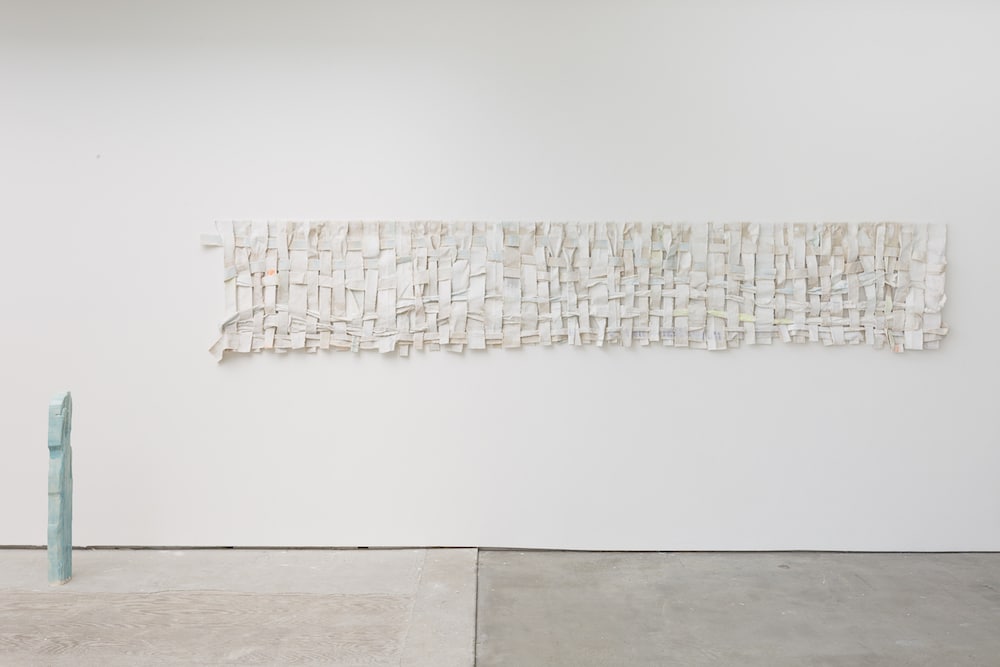

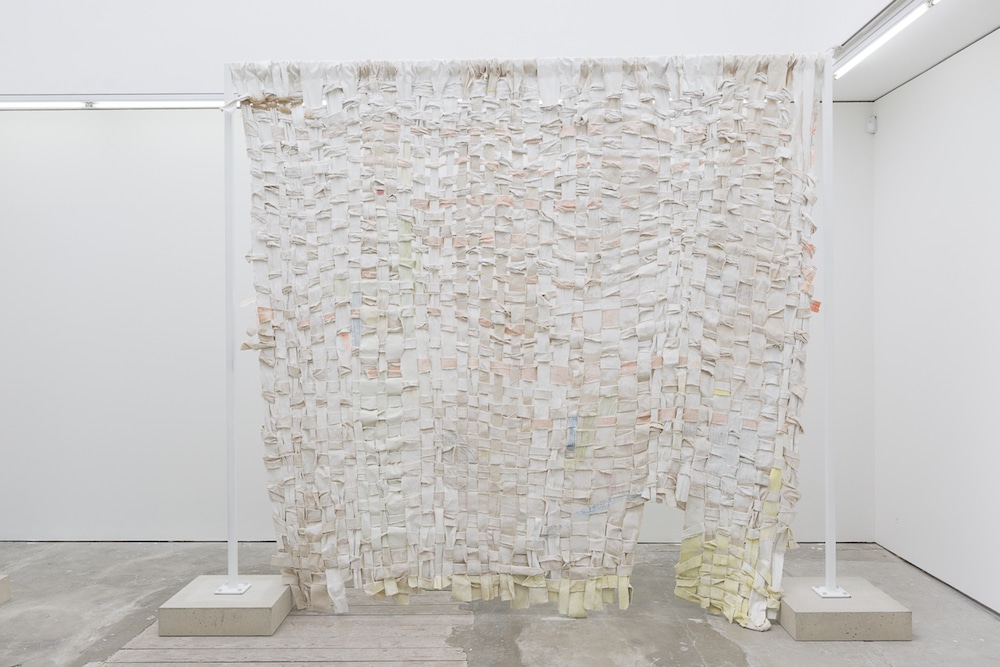

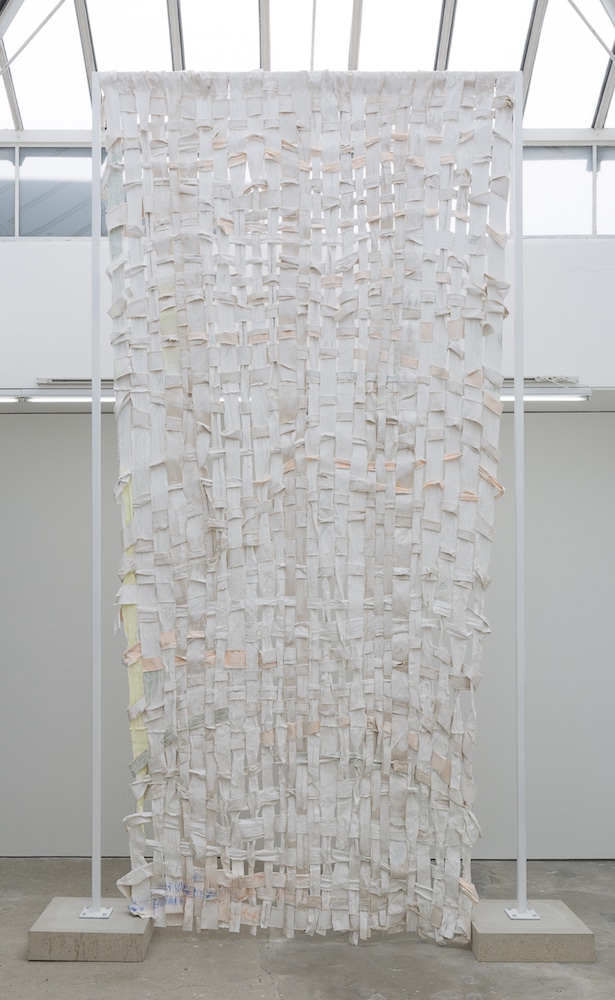

Carey’s fourth solo exhibition at Edel Assanti centres around a series of monumental woven canvases, suspended in the air on steel armatures as freestanding structures. Made from roughly woven strips of canvas that have been dipped in paint and woven whilst wet, their surfaces are then worked and reworked with paint, colouring pencil, and thread. Carey’s process imbues an aesthetic revealing wear and tear, evidencing time, as well as mental and physical labour. Despite bearing no discernible narrative, in medium and appearance they recall folk-traditions of recording collective histories through tapestries and quilt making.

The monumentality of the installation subverts the cloth’s ephemeral, domestic connotation. Standing as objects in space, the fabric sculptures have a strong physical presence, reaching the heights of the gallery; yet the loose, open weave allows light to pass through. Escaping the formal rigidity of woven structures, instead the works possess a rhythmical fluidity and raw simplicity, tapping into a sculptural vocabulary traditionally the preserve of heavy materials.

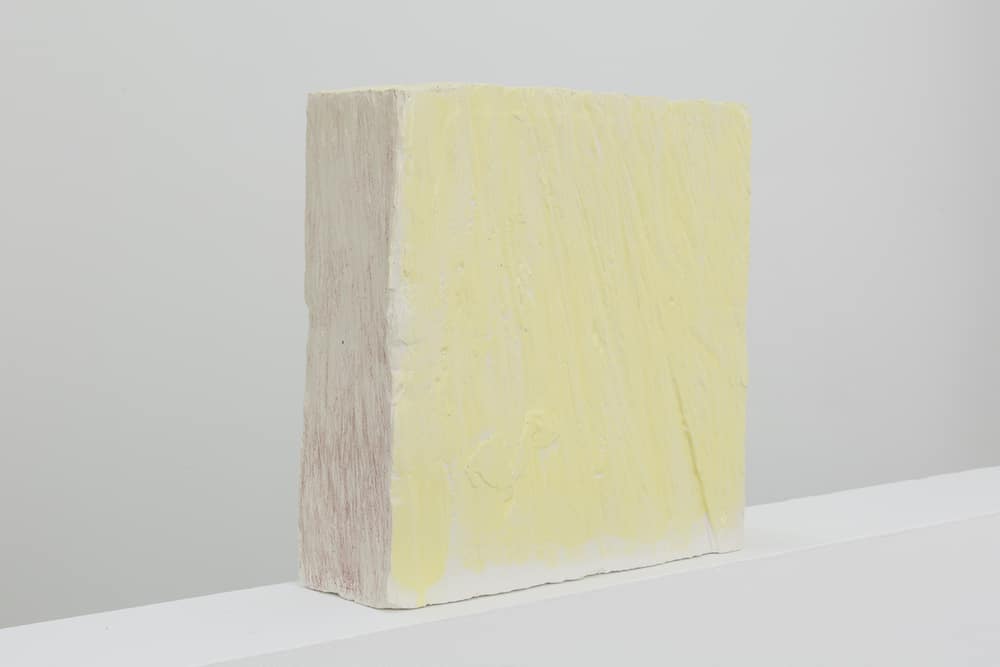

A number of floor-standing ceramic sculptures punctuate the space, infused with accents of colour mirroring the energetic impressions on the surfaces of the canvases. These works were cast from 100-year-old timbers that have been reused repeatedly in the artist’s practice. Their long history is etched into their weathered surfaces in a patina of cuts and marks that is captured in the cast ceramic sculptures, giving them a sense of objecthood. These small totemic works at once testify to humble origins, whilst also possessing an archaeological beauty.

Frieze Sculpture

Regents Park 2019

Edel Assanti is pleased to announce Jodie Carey’s work Cord will be featured in the 2019 edition of the Frieze Sculpture Park. Cord is a three metre high bronze work, anchored to the ground by a small concrete base.

Carey creates Cord through a technique she refers to as earthcasting: the artist buries a length of thick rope in the ground, using the space left once it has been excavated as a rudimentary mould, into which she pours bronze. When the liquid metal is poured into the raw earth, the soil cracks instantly as the bronze meets the earth’s moisture. Once it has been dug up, the sculpture memorialises the path of the metal as it spurted through the soil in vein-like tributaries.

Cord conceptually follows Carey’s site-specific commission for her acclaimed 2018 exhibition at Foundling Museum, in which she produced a floor to ceiling bronze sculpture using the same technique. This body of work is inspired by the Foundling Museum’s unique story of maternal love, loss and separation – the title Cord referencing the unbreakable bond between mother and child.

Carey’s recent practice reconsiders what constitutes a monument, asking how material can convey the true idiosyncratic experience of memory. Despite being materially strong, Cord has a brittle, fragile appearance. It seeks to make visible the fragility of relationships that are so fundamental to human existence, questioning whether such bonds can ever be broken.

The Foundling Museum

London

The Foundling Museum presents a new series of site-responsive installations by British artist Jodie Carey, commissioned by the Museum for display in the exhibition gallery and among the historic Collection.Carey’s response to the history of the Foundling Hospital has been to create a series of striking works that explore themes of love, loss and trace. Imbued with a sense of remembrance, these sculptures encourage visitors to reflect on the thousands of children who passed through the Foundling Hospital from the 1740s – 1950s, and the fragility of human life and relationships.

Drawing inspiration from the eighteenth-century fabric tokens left by mothers with their babies at the Foundling Hospital as a means of identification, Sea is a large-scale installation for the Museum’s exhibition gallery. Sea is formed of hundreds of swatches of fabric that have been dipped in liquid clay and fired to create delicate, white ceramic fragments that cover the gallery floor. During the firing process, the fabric burns away leaving only a trace of its weave and pattern, echoing the fragility of the textile tokens which are one of the few remaining and tangible connections between each mother and her child. The mothers’ intense feelings of separation and loss find a visual analogy in Carey’s vast ceramic outpouring. However, despite its overwhelming scale, Sea asks the viewer to recognise the detail of each unique cast and to see each as a small memorial and an act of remembrance.

Among the Museum’s historic Collection on the first floor, two monumental works explore ideas of memory and time. Found is formed of 18 life-size, totemic sculptures that crowd the Anteroom, each cast from the void left by rolls of fabric buried in soil. Found creates an environment that feels both natural and sacred, and suggestive of a ruin or archaeological find. The poured plaster bears traces of the land in which the sculptures were cast – centuries of soil, stones and plant roots. This earth-bound process resonates with the elemental nature of the Foundling Hospital narrative of love, loss, hope and survival. In casting bolts of fabric, Carey references the significant role that cloth played in the Hospital’s story – as emblems of hope for the mothers, methods of identfication for the institution, and routes of employment for the children – while final marks made by the artist using tailors chalk, are suggestive of storytelling.

Cord, displayed in the Foyer, is a delicate and slender bronze sculpture that stands floor to ceiling. Cast in bronze from cord buried in the earth, the sculpture appears both fragile and brittle, its contorted appearance belying its material strength. Referencing not only the bond between mother and child, but also the relationship between institution and foundling, Cord seeks to make visible the fragility of relationships so fundamental to human existence, and questions whether such bonds can ever be broken.

These commissions form part of the Museum’s 2018 programme of exhibitions, displays and events to mark the centenary of female suffrage, by celebrating women’s contribution to British society, culture and philanthropy from the 1720s to the present day.

Edel Assanti

London 2017

Edel Assanti is pleased to present Earthcasts, Jodie Carey’s third exhibition with the gallery.

Fifty vertical earthcast sculptures populate the gallery, at once industrial and abstract whilst also organic and evocative. As with much of Carey’s recent works, the monumental scale of the works belies the fragility of the plaster, soil and colouring pencil used in their making. Their vertical stance recalls the timelessness of standing stone monuments, evoking a primitive connection with the substance of life. Carey’s use of scale is intentional – the sculptures tower over an individual, whilst still posing a relationship with the human body, oscillating between the figure and form of a tree trunk through their knotted, scarred surface.

Carey’s recent work has explored the most basic and fundamental methods of art-making, including carving, weaving and wall-drawing. The earthcasts are produced by casting directly in the ground: Carey buried lengths of decades-old salvaged timber in the soil, lifted them out to form rudimentary moulds. Into these imprints she pours plaster which, once solidified and excavated, bears remnants of the soil, stones and plant roots absorbed during this process.

Referring to soil as the skin of the earth, Carey’s interest in soil as a material is born out of its essential relationship to life and simultaneous ability to embody death. Its complex constitution combines minerals, water, air and the decaying matter of once-living things. In this way the earthcasts continue Carey’s engagement with notions of mortality, memory and modest commemoration of everyday ritual, aligning with her previous artistic mediums of bone, ash and dust.

Both before and after the casting process, Carey makes her own impression on the materials of these sculptures – beforehand, through discreet cuts and reliefs carved into the timber; afterwards, through delicate, pastel coloured pencil shading, a recurrent approach in Carey’s work, suggestive of naive mark-making and the universal human urge to make an impression on our surroundings.

porcelain, ash

dimensions variable

Installation view The Observer Building, Hastings 2016

Galerie Rolando Anselmi

Berlin, 2016

Galerie Rolando Anselmi is pleased to present an exhibition of new work by Jodie Carey. This exhibition weaves together ideas surrounding time and timelessness, to explore traditions of commemoration and remembrance. Drawing influence from the land and ancient images of stone circles, Carey assimilates the geometric simplicity and large-scale directness to create works that seek a material response to the idea of sculpture, as a carrier for collective memory.

Early Old comprises of two plaster sculptures cast directly in the ground. The plaster surface bears all the traces of the land in which they were made, engaging with the earth itself – centuries of soil, the skin of the earth, without which there would be no life. As with previous series, the handmade materiality and material roughness of the works is contrasted by the vulnerability of the ephemeral materials Carey employs in their making. Primarily physical works, the bold simplified forms convey a sense of monumentally, their vertical stance akin to prehistoric ancient monuments. They echo the immortality of standing stones and suggest a primitive connection with the substance of life. Final marks made by the artist, using paint and colour pencil, emphasis the roughly hewn forms.

In sharp contrast to the large simplified forms of Early Old is Fallen, a thousand porcelain leaves which litter the gallery floor. This juxtaposition of size, scale and material between the two sculptural works emphasis further the fragility and delicacy of the ceramic leaves. Each leaf is unique, created by dipping its skeleton directly in slip. After firing, the ashes remain immortalised within the porcelain body – the elegiac, transient nature of falling leaves captured forever in ceramic.

Untitled (patchworks) are created from linen and canvas dipped in plaster and worked on using paint and colour pencil. Despite bearing no discernible narrative, in medium and appearance, they recall folk- traditions of recording and recounting collective memory through tapestries and quilt making. The simple mark-making evocates wall or cave drawing, the most ancient practice of recording human history and memory.

The contemplation of mortality, of memorials and of the passing of time, is frequently addressed throughout the history of art. Jodie Carey eloquently continues this tradition, utilising ideas, materials, processes and techniques which weave together elements of the contemporary and the traditional, to create compelling and poignant works, full of elegance, gravity, commitment and poetry.

Edel Assanti

London 2015

Edel Assanti is pleased to present an exhibition of new work by Jodie Carey.

The exhibition explores ancient yet timeless traditions of commemoration, drawing inspiration from disparate cultural sources from Scandinavia to South East Asia, the Neolithic to modern. Carey discernibly assimilates these practices in the creation of the three series that comprise the exhibition: large-scale plaster urns, wall based canvas hangings and pencil wall drawings.

As with previous series, the monumentality of the works in the exhibition is contrasted by the vulnerability of the ephemeral materials Carey employs in their making. The large sculptures develop ideas explored in work produced for an exhibition at the Freud Museum last year. Made of plaster, they begin as solid blocks which are then hollowed and carved by hand. The removed plaster rubble litters the floor surrounding the urns, intentionally tying the sculpture to their process of creation. The quiet reverence of these imposing anonymous forms recalls the Plain of Jars, a prehistoric burial site in Laos where thousands of megalithic jars are clustered together.

Carey produces the wall hangings by dying and dipping long strips of canvas in plaster, weaving them together whilst the plaster is in its drying stages, further developing the surfaces using pencil shading. Despite bearing no discernible narrative, in medium and appearance they recall folk-traditions of recording and recounting collective memory through tapestries and quilt making.

The polymorphous wall drawings are executed using colouring pencils, a medium selected for its naivety and delicacy. The pastel colours and idiosyncratic nature of colouring induce childhood nostalgia, whilst the act of wall drawing itself refers to the most ancient practice of recording human history and memory. Taking the character of memory itself, these are erasable, fluid artworks, evolving and adapting to each situation in which they reappear.

The Freud Museum London

2014

Untitled (love and loss), 2014, plaster, concrete, moss, dimensions variable

Carey’s two-piece sculpture, commissioned by the Freud Museum specifically for this exhibition, incorporates the themes of loss and longing that Carey has explored in previous works, but also love and dependency. Two dishes, one weathering, one protected, they relate and respond to each other. Their simple forms recall some of the antiquities in Freud’s collection whilst their placement in the garden sites them in the context of Sigmund and Martha’s home.

Carey writes that ‘the work explores the dualism, which runs throughout Freud’s thinking, the combination of opposites and dichotomies that for Freud drive all of human sexuality. The two pieces serve to highlight the conflict between Eros, the life instinct and Thanatos, the death drive. But they also speak of the grief and loss inherent in Freud’s personal collection of antiquities, which began in response to the death of his father. Their position in the front garden unites them with the history of the house, a symbolic pair, recounting the passionate courtship between Martha and Freud, their enduring marriage and Freud’s death, twelve years prior to Martha.’

The pieces retain Carey’s chisel marks, revealing the artistic process of creation and also the natural process of erosion. Whilst one of the sculptures has received a protective coating, the second has been left exposed to the elements. Over the course of the exhibition this second sculpture will wear with the weather: moss and weeds impregnating its surface, colours changing over time, its surface evocative of forgotten gravestones in derelict graveyards. Hand carved, they are imbued with a sensual, tactile quality. Carey’s two-piece work explores life and death, love and loss, desire and rejection.

Sophie Leighton

Curated by Manuel Wischnewski

Neue Berliner Räume

2014

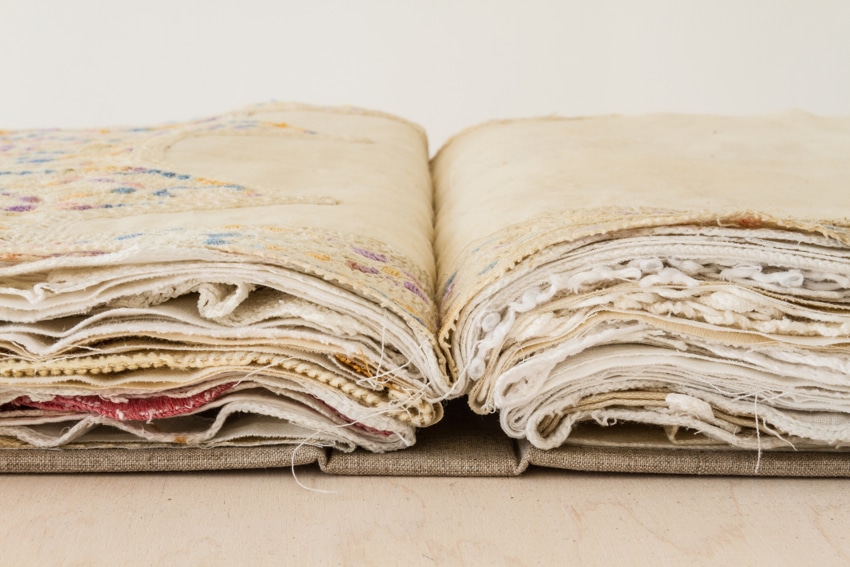

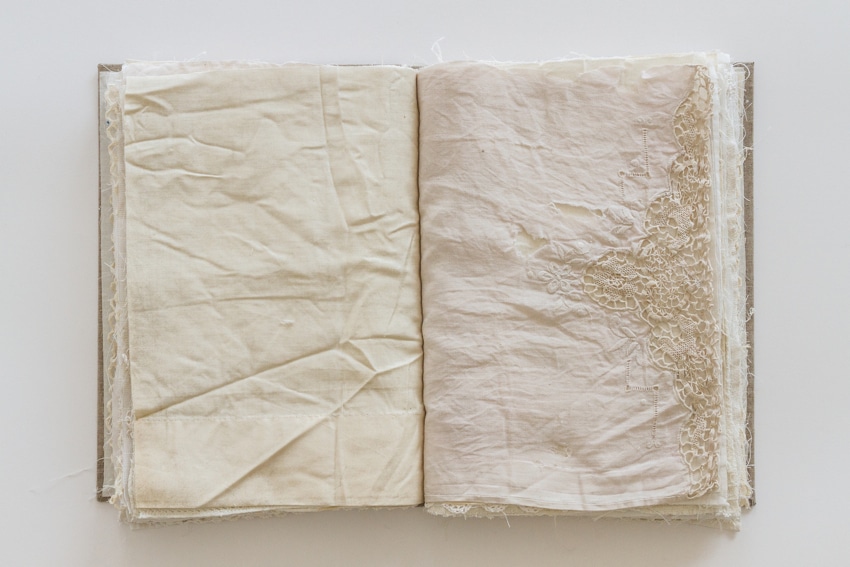

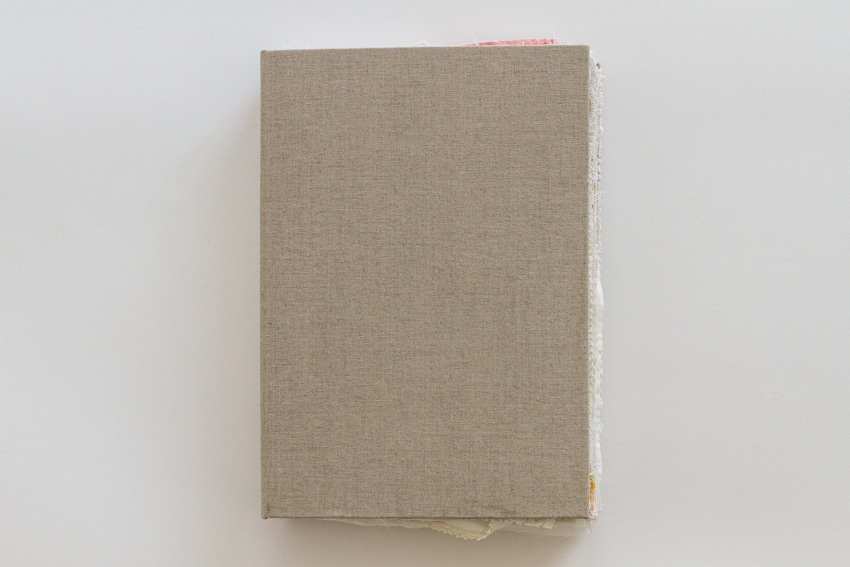

a recollection, 2014, portrait linen, bookboard, antique linens, (each) 37 x 27 x 6cm

What do we do with memory and its objects? Do we hold on to them, or do they hold on to us? Remnants of memory – be it a material object, a feeling or an empty space – challenge us to find a way to deal with them. To show, to hide, to safeguard, to tell – differently, or anew? When we use the word memory, we always mean something different.

Six artists have been invited to consider the question of memory. The exhibition does not remain on the level of the abstract, however, but opens out to the concrete space of the biographical: the personal archive. The works of the participa-ting artists relate – either directly or through association – to the estate and history of the curator’s grandmother, Elisabeth. She lends the exhibition its title, as well as its form and the questions it raises. The works delve into her archive of memorabilia, its objects and materials, drawing on the private and the shared, the intimate and the gaps that the intimate leaves behind. The exhibition moves between the historical, that which has only just slipped into the past, and that which still persists in the present.

Tracing this axis, the contributions of the artists offer up a space for projection and association. Through its mode of appearance and being, each concrete memory tells us something of the significance of memory itself. Not only specific histories, but also the act of remembrance itself are made present in these objects: memory as a culture and a practice, as an attitude, and not least as the search for a fitting place to locate the past in the present.

What does it mean to remember? It always means something different.

History projects itself into the present through objects – often the most humble of objects – as an essence. Or as a scarcely discernible hint. Regardless of whether we hold onto these objects or give them away, they bear the sober proof that something was there.

The immediacy of the past lies in its materiality. We touch things, and touch doubles itself. My touch is layered over that of another person, which was layered over the touch of another person before. Everything is folded into everything else and borne within the object itself.

Precisely in the moment when we try to move closer to everyday objects, history appears not as a grand narrative, but as an alternative history, a parallel recounting. The coexistence of these multiple narratives reminds us that perhaps every telling of history is nothing more than an attempt. A memory does not come into being of its own accord, but must be wrested from what remains, as a form of work and a process.

The past surrounds us. Even if we are not fully aware of it, it is constantly unfolding, colouring our perception. Even things forgotten are present, and things never acknowledged are just nearby. Almost perceptibly, these things are written into the here-and-now.

In a moment of remembering, we stand in for something. We perform a service. Something becomes vi-sible and shows its face. This thing becomes palpable in its scope and its grounding, in its effect and its affect.

Histories are always connected to their narrators, to the memories of those who look after their memories. Someone or something else always steps into the gaps and fills them, often not completely, but hazily, and inexactly. Narratives are carried by us and for us, by us and for others, into another moment. But it is never quite possible to pinpoint precisely why we remember and what exactly takes place when we do it.

Old stone monuments come to mind, the kind one finds in small villages. Their language is rough and clear, balancing the evasiveness of memory with something firm and solid. They ground memory with a concrete place, providing it with a form and a materiality of its own. The attempt to ward off dissolution with such a monumental form touches at something deep and ancient. These stones carry themselves. Always on the point of falling, they support one another. No mortar fits them toge-ther. They hold themselves in place with their weightiness, and their mass presses against the ground.

In some places, the stones are smoother and flatter. Here, they have faced decades of wear and tear. The stones’ rough and uneven surfaces are buried in the ground, twisted inwards and hidden. They only become visible when one prises a stone away from the earth.

Stones on graves: old rituals. A knocking – the sound when stone is laid on stone.

Perhaps there are reasons for why we prefer one image over another. We always find in the chosen image a confirmation that other images do not yield. Because it tells one history that we know and consider to be our own. This history becomes an image that stands in for all other images.

The backwards glance harbors the risk of loss. We create out of memory, and yet lose something else at the same time, even as we maintain our gaze. We want to affirm ourselves, and so we thrust ourselves towards and into a memory. Yet the memory, when it appears, has changed.

The challenge exists in risking something; in giving something up – letting go of an image, and finding, in its place, something else entirely

Things become icons. Out of these icons our narratives are created, and inside them we trustfully place our images. Strange is the thought, however, that an object should speak for a person. Everything that it hints at might be only an assumption, a shadowy version of something that was.

All that we see is the opacity of things. And so our gaze – and with it, the object of our gaze – falls into uncertainty. What traces are left behind by history? What traces are left behind by our gaze? Beneath every surface lies a second surface, and a third.

When narrative dissolves, images fall apart from one another and into a new order. The ambivalence of things rests in the intimacy of their address, emerging in the puzzles that they pose.

We seek a dialogue with those who are present absences. What questions do we direct to them? What questions should we begin with? – and what questions should we begin to ask ourselves?

Remembering is a negotiation with ghosts.

The closer we move to a memory, the more unclear its image becomes. Tensions do not dissolve, but only transform. Perhaps one learns to reconcile oneself with this uncertainty, perhaps not. What remains is a dialogue without a partner. One can only answer oneself differently, each time.

Before an image is unraveled, one must first possess it.

Manuel Wischnewski

2014

Hå gamle prestegard

Norway

In recent years, Jodie Carey’s practice has developed in interest in abstraction as well as dematerialization and a renewed interest in working with textiles. The works produced for this exhibition take into consideration both the landscape and the history of the area.

Carey drew inspiration for this work directly from the site of Hå. When exploring the site, she came across didactic materials discussing the history of the site. These materials mentioned that in the fifteen hundred years since people had been buried on site, wind and weather had eroded their bones, cloth and wood. These precise materials, in various forms, have been a fixture in Carey’s practice for many years.

Carey has long been interested in issues of time, memory, commemoration and ritual. Her work often features ordinary items that relate to these concepts in various ways including: flowers, lace, chiffon, bone and newspapers. Her interest is in the consistency of such materials, as part of the everyday fabric of our lives; but also on their fleeting materiality as individual objects.

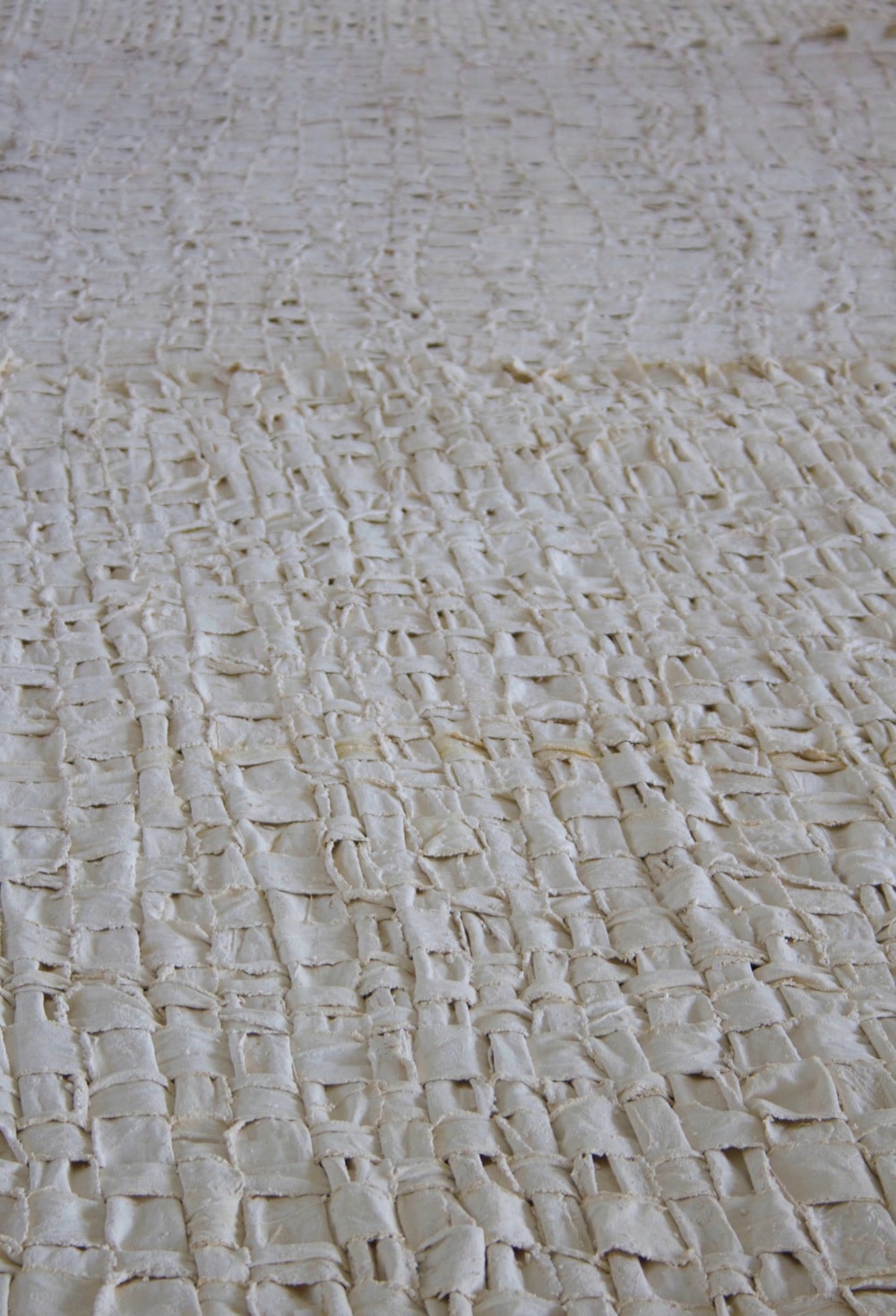

For her exhibition at Hå, Carey has produced two large-scale, minimal in appearance yet incredibly labour intensive installations. On the ground floor, a landscape of woven canvases is carefully scattered about the space. These woven canvases are a new development in Carey’s practice. She spent weeks tearing 100 metres of canvas into strips. She then dyed and dipped the strips in plaster. Once saturated, she carefully wove the strips together to form the large canvases in Untitled (Landscape). This work is multi-layered in its references to craft, tradition and routine.

A large portion of the remains found at Hå were female, and these woven canvases are a subtle yet deliberate attempt to restore female craft traditions, like weaving, to the site. The delicate colours used to dye the canvas mimic the colours of the surrounding landscape. Carey wanted the exhibition to relate to the surrounding landscape at Hå, immediately perceivable through the gallery windows.

Carey studied textile design in university and abandoned this practice to work in sculpture. Recently, she has returned to her foundations in textiles. This return to her use of textiles, has liberated Carey from some of the constraints she began to feel with sculpture.

Carey is concerned with being an artist as communicator, and therefore with being able to physically make the work herself. As such, it is extremely important to her that she be able exercise control over the process, much like the ‘process art’ of the mid-1960s.1 In Carey’s works, the end product always directly relates to the process.

A recent work by Carey, entitled Untitled (Bouquet) signalled a return to these roots in textiles and is an important precursor to the works produced for this exhibition. Carey used a bouquet of flowers as the start of this work, using the colours from the bouquet to make dye for the cotton yard that she then crocheted into a hanging, sculptural object. The bouquet’s rainbow of colours generated a method of using ‘found’ colour in her practice.

The canvases produced for Hå employ some of these same colours – with their proximity to the landscape highlighting the broad palette found in nature from the setting sun as it reflects on the water to the shoreline and surrounding fields.

In the upper gallery, Carey was interested in producing a work that responded directly to the unique atmosphere. The atmosphere on the upper level is exactly the same as that outside. Here, Carey wanted to work with paper, as it would respond to the environment by degrading over time, just as the other natural materials on site had. For this work, Carey decided to use newspaper, a material that has long formed part of her practice.

Carey sourced one tonne of newspapers all of which had been read. She then spent four days burning the papers down and salvaging the resulting ash. This ash was then carefully sieved to produce the fine dust of Untitled (Newspaper dust). This choice of materials again restores one of the destroyed materials, wood, to the site, albeit in its most dematerialised form.

In recent years, Carey has produced several works using dust, a material she has embraced for its workability and ability to occupy space. This new work at Hå is her largest work to date using newspaper. Her previous works in dust have included materials such as blood and bone that have been finely ground to produce expansive site-specific fields of colour in the buildings where they were exhibited. The selection of these materials points to a process that very much interests Carey – that is, these essential elements of life whose repulsive nature is undermined by their delicate texture and tactile nature in the form of dust. Carey’s choice of materials (blood, bone and newspaper) deliberately allude to the impermanence of life.

Dark night by daylight, the exhibition’s eponymous work, appears as an unremarkable linen canvas from afar. However, it is another example of Carey’s sensitive approach to materials and process. This work is composed of hand-woven linen thread that has been dyed in a gradient, using the newspaper ash in Untitled (Newspaper dust). This small work is mounted on board, rendering the gradient more visible. This grey scale mimics a flow of time, dark fades to light, just as day fades to night.

The works in Dark night by daylight signal the thoughtful approach Carey had to making works that relate both to the site of Hå, and particularly the women who once lived there. These works restore some of the lost materials and traditions to the site, in precarious forms that underscore the timelessness of the transitory nature of our everyday lives. These works also take into account the current landscape of Hå through their site-specificity and their sensitivity to the surrounding landscape of colours and materials.

Text by Claire Shea

_____________________________________________________________________________

1 Process art intended to overcome the traditional oppositions of form and content and of means and

ends – to reveal the process of the work in the product, indeed as the product. The second imperitive of some Process art was to overcome the no-less-traditional opposition of figure and ground, of a vertical image read against a horizontal field. (Hal Foster et al., Art Since 1900 (London: Thames & Hudson, 2004), 535.

2013

curated by Neue Berliner Raume

Installation view Anantomical Theatre Humboldt University Berlin

Throughout her work, British artist Jodie Carey has concerned herself with the complex dynamic between remembering and letting go. Carey’s works represent a bid to trace the idea of mortality while simultaneously setting it against a moment of retaining. The result is an obscuring of the lines that usually divide documentary archive and poetic, narrative elements. In the case of Carey’s works, these two seemingly opposed methods of recording are carefully woven together.

The question of material sits at the core of Carey’s work. The artist uses materials that are at times mundane – dust or cigarette ash – while at other times loaded with symbolic meaning; blood or bone fragments. These materials, however, consistently transcend the level of pure materiality: Carey is interested in materials that derive from the actual object or moment that she is concerned with. Using this approach, Carey attempts to create authentic moments of memorialisation. Much like religious relics, the artist’s works are not merely a symbolic representation but rather the repository of a material essence. In this duality, we see the reinforcement of a remembering that is so typical of Carey’s work.

But Carey’s works never function as mere replacements for that which is disappearing. They refrain from being static memorials or pure aesthetic representations of what has been lost. The works are deeply melancholic, referencing an emptiness and a loss. The artist thus moulds her work into being a visible sign for this underlying mortality rather than shrouding its ubiquity. With this approach, Carey renders the realm of the lost an invisible and intangible part of her work. The artist’s aspiration to find an appropriate presentation of the material reflects our own quest for a meaningful – perhaps even dignified – treatment of those moments and objects that we strive to secure in our own memory.

With Shroud, a work specially conceived for the Veterinary Anatomical Theatre (at Humboldt University), Carey manages to survey the site anew using as a baseline the subject matter of her work. In this way, the artist offers a complex reading of the particular atmosphere of the Theatre and her own work.

The Veterinary Anatomical Theatre is one of the most significant buildings on the Berlin architectural landscape. Designed by Carl Gotthard Langhans at the request of King Friedrich Wilhelm II of Prussia, the Theatre was built between 1789 and 1790 – concurrent to the construction of the Brandenburg Gate, also designed by Langhans. The Auditorium – topped off with a dome and gracefully tiered benches – forms the focal point of this architectural masterpiece. The outstanding example of Berlin Neoclassicism is located on the historic Humboldt campus between Invalidenstrasse and Friedrichstrasse. The Veterinary Anatomical Theatre remains the oldest standing academic building in Berlin and so occupies a pre-eminent position in the cultural history of the city. Initially opened as part of the royal school of veterinary medicine, the Theatre was later subsumed into Humboldt’s faculty of veterinary medicine. From this point on, it served as a locus of university teaching and research. Between 2005 and 2012, the building underwent an exemplary renovation. Today, the Veterinary Anatomical Theatre is used by the Hermann von Helmholtz-Zentrum für Kulturtechnik – part of Humboldt University. Shroud is the first contemporary art show in the building’s history.

For this site-specific installation, the artist has employed powder that she painstakingly quarried from bones. The finely applied bone dust conveys an impression of fragile lightness that is contrasted by the work’s extensiveness and sheer mass: over 250 kg of bone powder spread over nearly 300 sqm of space. The formal outlines of the work appear to flow into the adjacent rooms and old library from that very spot in the auditorium where once the dissecting tables were moved up from the cellars. Accepting and adopting the outlines of the building, the installation respects the architectural integrity of the historic ensemble both on an aesthetic and conceptual level. In this way the building does not simply act as a mere backdrop to the exhibit but is rather foregrounded as an element of the artistic work itself. With Shroud, Carey responds in full awareness to the space and instead of simply overriding that which is already there, the artist speaks both with and through the space.

The installation makes a bid to supply the space with an atmospheric charge and to make visible that which is no longer accessible. It is a bid made taking into consideration the prolific history of the site. Delicately laid across the floor of the space, the finely ground bones function as a subtle reference to this rich past and through this the artist infuses the space with a moment of remembering, a moment of holding on. Yet ultimately Carey’s work expands beyond its immediate, concrete context to develop a narrative about the historical reach of a location in overall terms.

On a thematic level, Shroud also reflects the spirit of the Theatre as well as the historic uses the site has been put to. Just as Carey’s work has confronted the mechanisms and representational modalities of mortality, the Veterinary Anatomical Theatre has been a site devoted to the research of these precise issues. It is a site where work and space intersect and engage in dialogue – and it is this intersection of work and space that allow the installation and spatial context to connect in an autonomous position. The Theatre is a location where the basic questions about the dynamics of life have always been the main focus. And so – almost of its own accord – the Veterinary Anatomical Theatre imbibes Carey’s delving, melancholic work. The history of medicine in the early modern and modern periods was about more than just the bald discovery of facts. It was too a not uncontroversial reflection of a particular worldview, a particular view of the self. And it is in this way that Carey’s approach continues to oscillate between delving and poetry, between unalloyed depiction on the one hand, and interpretation on the other.

With Shroud, Jodie Carey has created a work that seizes upon her subject matter at a site that – like no other – lends itself to her narrative. Shroud is thus a work that underscores the questions that have left their imprint on both the site and the artist herself.

Manuel Wischnewski

Galerie Rolando Anselmi

2013

Neue Berliner Räume and Galerie Rolando Anselmi are pleased to present Immemorial, the first solo exhibition in Berlin by British artist Jodie Carey. The exhibition takes place both in the gallery and at a further location which will be announced shortly.

In all her works, Jodie Carey is concerned with the complex dynamics of remembering and letting go. The artist’s approach is marked by her desire to trace the vulnerability of mortality while at the same time attempting to retain something lasting. In doing so, Carey obscures the lines dividing a pure documental archive from a poetic narrative as she carefully weaves these two parts together in her work.

The question of the material sits at the core of Carey’s work. The artist uses materials that are at times mundane — like ashes from a cigarette or dust — and at other times highly loaded with symbolic meaning, like blood or bone ashes. Almost always, Carey is interested in a material that is derived from the actual object or moment that she is concerned with. This approach reflects Carey’s attempt to create authentic moments of memorializing. Much like religious relics, the artist’s works are not merely a symbolic representation but more so, the repository of a material essence. In this duplicity, we see the reinforcement of a remembering that is so typical for Carey’s work.

The question of the adequacy of a particular way of remembering is always at the centre of Carey’s interest. The artist’s aspiration towards an appropriate presentation of the material reflects our own quest for a challenging and meaningful, perhaps even dignified treatment of those moments and objects which we want to secure to our memory. More than anything, the artist’s works are always a reference to what is lost in this process, to what is not included. Through her approach, Carey renders this loss an invisible, intangible part of her work.

Elegy, 2012, A room never meant to be, Installation view Postfuhramt Mitte, Berlin

Curated by Neue Berliner Raume

Postfuhramt Mitte, Berlin

2013

Neue Berliner Räume is pleased to present the special exhibition A room that was never meant to be, featuring works by British artist Jodie Carey.

A room that was never meant to be takes place on one afternoon only and was conceived especially for the space of the exhibition.

Located in one of the most eminent buildings of Berlin’s old centre, the exhibition space was originally designed as a headlight for a subjacent hall, bringing natural light into the lower parts of the building. With the decision to close the hall’s ceiling after the Second World War, a hidden room was created in the attic of the building. As such, this room was never meant to be. It has not been used publicly in the years of its existence and with the pending renovation of the building complex that houses the space, the room will soon disappear again.

Jodie Carey’s Elegy series (2012) consists of five prints from original photographic glass plates that were produced in the 1920s. Glass plates were used as photographic material before the rise of celluloid and were at the centre of the rapidly developing photography technique. Today, their usage has almost entirely faded and original plates are extremely rare. The five Elegy plates depicting classic flower arrangements emerged during an attic clearance and were subsequently acquired by the artist. In an attempt to save the fragile and damaged photographic traces on the plates, the artist decided to carefully produce digital prints. By choosing not to “clean” these prints from the signs of the plate’s material damages, the artist saw a possibility to memorialize the entire history carried by these plates; a possibility to uncover not only the fading images once inscribed onto the plates but also the marks of their history. Making these blemishes visible is a way of being truthful about these objects and the whole depth of their story.

In the context of this particular presentation of the works, the five prints refer to a loss. Inside a room stripped of much of its former splendor, they are filling a void — if only momentarily. As a traditional symbol of decay and timeliness, the floral arrangements poignantly echo a sense of melancholy. The tangible history of the space and the ever present signs of transience work towards a subtle intertwining of work and space. What emerges is a temporary dialogue that points to two histories marked more than anything by their slow but graceful withering.

Manuel Wischnewski