Curated by Manuel Wischnewski

Neue Berliner Räume

2014

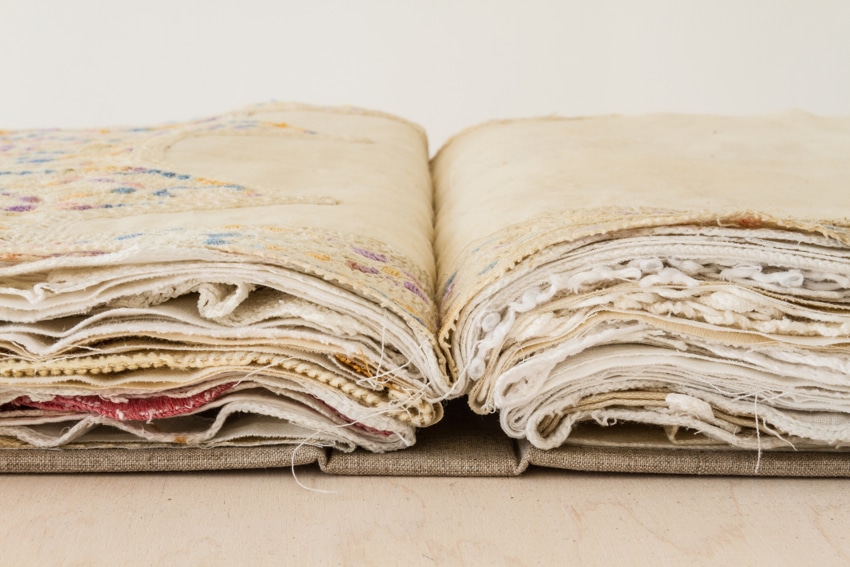

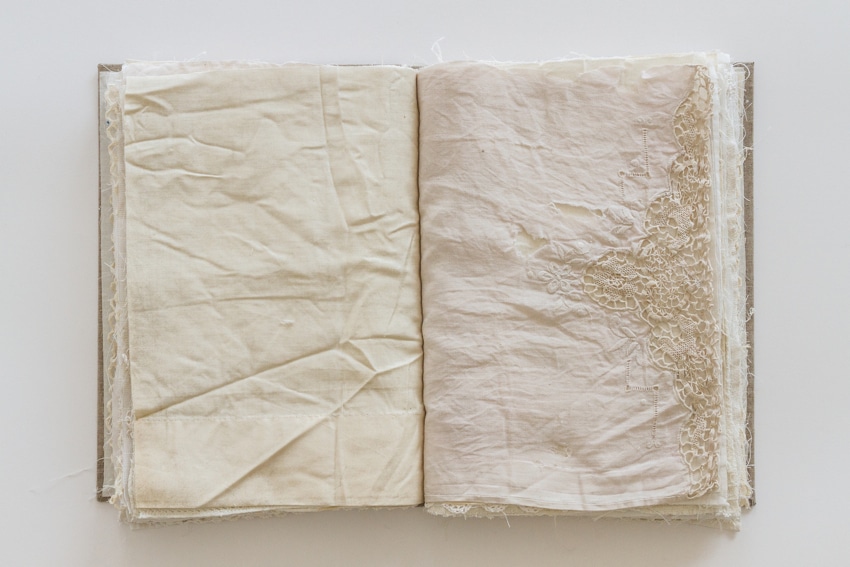

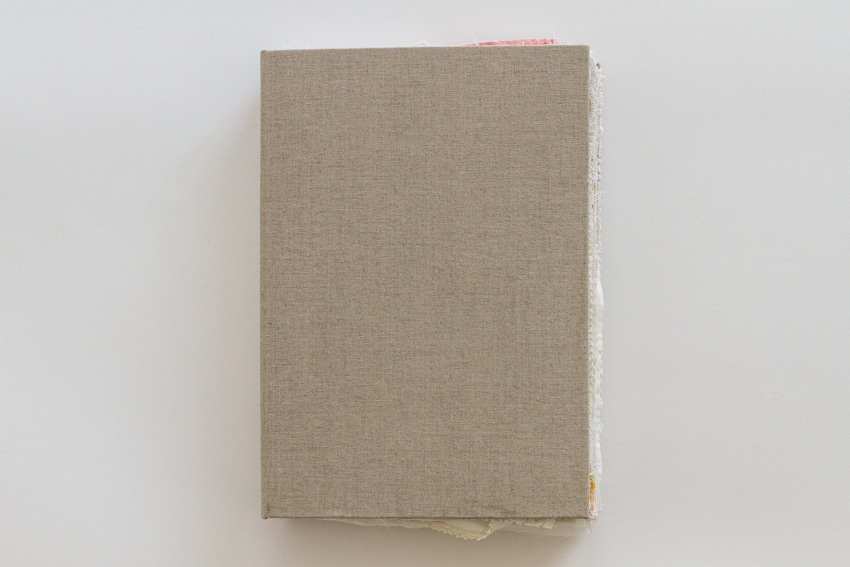

a recollection, 2014, portrait linen, bookboard, antique linens, (each) 37 x 27 x 6cm

What do we do with memory and its objects? Do we hold on to them, or do they hold on to us? Remnants of memory – be it a material object, a feeling or an empty space – challenge us to find a way to deal with them. To show, to hide, to safeguard, to tell – differently, or anew? When we use the word memory, we always mean something different.

Six artists have been invited to consider the question of memory. The exhibition does not remain on the level of the abstract, however, but opens out to the concrete space of the biographical: the personal archive. The works of the participa-ting artists relate – either directly or through association – to the estate and history of the curator’s grandmother, Elisabeth. She lends the exhibition its title, as well as its form and the questions it raises. The works delve into her archive of memorabilia, its objects and materials, drawing on the private and the shared, the intimate and the gaps that the intimate leaves behind. The exhibition moves between the historical, that which has only just slipped into the past, and that which still persists in the present.

Tracing this axis, the contributions of the artists offer up a space for projection and association. Through its mode of appearance and being, each concrete memory tells us something of the significance of memory itself. Not only specific histories, but also the act of remembrance itself are made present in these objects: memory as a culture and a practice, as an attitude, and not least as the search for a fitting place to locate the past in the present.

What does it mean to remember? It always means something different.

History projects itself into the present through objects – often the most humble of objects – as an essence. Or as a scarcely discernible hint. Regardless of whether we hold onto these objects or give them away, they bear the sober proof that something was there.

The immediacy of the past lies in its materiality. We touch things, and touch doubles itself. My touch is layered over that of another person, which was layered over the touch of another person before. Everything is folded into everything else and borne within the object itself.

Precisely in the moment when we try to move closer to everyday objects, history appears not as a grand narrative, but as an alternative history, a parallel recounting. The coexistence of these multiple narratives reminds us that perhaps every telling of history is nothing more than an attempt. A memory does not come into being of its own accord, but must be wrested from what remains, as a form of work and a process.

The past surrounds us. Even if we are not fully aware of it, it is constantly unfolding, colouring our perception. Even things forgotten are present, and things never acknowledged are just nearby. Almost perceptibly, these things are written into the here-and-now.

In a moment of remembering, we stand in for something. We perform a service. Something becomes vi-sible and shows its face. This thing becomes palpable in its scope and its grounding, in its effect and its affect.

Histories are always connected to their narrators, to the memories of those who look after their memories. Someone or something else always steps into the gaps and fills them, often not completely, but hazily, and inexactly. Narratives are carried by us and for us, by us and for others, into another moment. But it is never quite possible to pinpoint precisely why we remember and what exactly takes place when we do it.

Old stone monuments come to mind, the kind one finds in small villages. Their language is rough and clear, balancing the evasiveness of memory with something firm and solid. They ground memory with a concrete place, providing it with a form and a materiality of its own. The attempt to ward off dissolution with such a monumental form touches at something deep and ancient. These stones carry themselves. Always on the point of falling, they support one another. No mortar fits them toge-ther. They hold themselves in place with their weightiness, and their mass presses against the ground.

In some places, the stones are smoother and flatter. Here, they have faced decades of wear and tear. The stones’ rough and uneven surfaces are buried in the ground, twisted inwards and hidden. They only become visible when one prises a stone away from the earth.

Stones on graves: old rituals. A knocking – the sound when stone is laid on stone.

Perhaps there are reasons for why we prefer one image over another. We always find in the chosen image a confirmation that other images do not yield. Because it tells one history that we know and consider to be our own. This history becomes an image that stands in for all other images.

The backwards glance harbors the risk of loss. We create out of memory, and yet lose something else at the same time, even as we maintain our gaze. We want to affirm ourselves, and so we thrust ourselves towards and into a memory. Yet the memory, when it appears, has changed.

The challenge exists in risking something; in giving something up – letting go of an image, and finding, in its place, something else entirely

Things become icons. Out of these icons our narratives are created, and inside them we trustfully place our images. Strange is the thought, however, that an object should speak for a person. Everything that it hints at might be only an assumption, a shadowy version of something that was.

All that we see is the opacity of things. And so our gaze – and with it, the object of our gaze – falls into uncertainty. What traces are left behind by history? What traces are left behind by our gaze? Beneath every surface lies a second surface, and a third.

When narrative dissolves, images fall apart from one another and into a new order. The ambivalence of things rests in the intimacy of their address, emerging in the puzzles that they pose.

We seek a dialogue with those who are present absences. What questions do we direct to them? What questions should we begin with? – and what questions should we begin to ask ourselves?

Remembering is a negotiation with ghosts.

The closer we move to a memory, the more unclear its image becomes. Tensions do not dissolve, but only transform. Perhaps one learns to reconcile oneself with this uncertainty, perhaps not. What remains is a dialogue without a partner. One can only answer oneself differently, each time.

Before an image is unraveled, one must first possess it.

Manuel Wischnewski